Katie Steedly’s first-person piece [The Unspeakable Gift] is a riveting retelling of her participation in a National Institutes of Health study that aided her quest to come to grips with her life of living with a rare genetic disorder. Her writing is superb.

In recognition of receiving the Dateline Award for the Washingtonian Magazine essay, The Unspeakable Gift.

Enter your email here to receive Weekly Wide-Awake

The Work

“Why write love poetry in a burning world? To train myself, in the midst of a burning world, to offer poems of love to a burning world.” — Katie Farris

The Project

I am an applied researcher living in Atlanta across the street from a beautiful, historically designated, renovated-so-people-can-live-there brick factory, the B. Mifflin Hood Brick Company. B. Mifflin Hood was an activist industrialist who stood against convict leasing, a prevalent practice in the post-Civil War United States.

I aim to tell the story of a space that brings together art, history, and activism. It will answer the questions: What can/does resistance look like? What role can/does art play in resistance, creating community, and pursuing justice? What can a building teach us as a conduit for history, testimony to justice, and substance of/for resistance?

After years of living next to the space and insightful conversations with the artist/activist couple who renovated it, the architect who redesigned it, and the artist who created the public art outside it. I am prepared to explore the space. I am ready to offer a love letter to art, history, and activism.

My Perspective

I shook in my boots my first day of teaching writing at a federal prison. I observed a lead teacher in the program on several occasions to make sure I was ready to have my own class or to decide if I wanted to teach at all. I attended a reading where student writers — men who were incarcerated — shared their work. I immediately connected with their stories.

I designed my classes around the concept of gratitude. I felt the power of story and that knowing and sharing our stories makes it impossible, or at least more difficult, to be cruel and inhumane. Knowing and sharing our stories makes it easier, as Ross Gay writes, to find what we love in common. In doing our work together — me and the 18 or so men between the ages of 18 and 80, mostly men of color, some with college degrees and some who had not finished high school — keeping daily gratitude lists, writing weekly short gratitude-focused essays, and sharing our work — we were finding what we love in common. We were learning to write love letters in a burning world — week after week, month after month, year after year.

They call incarceration being inside the fence. I learned a few things while teaching

inside the fence. I learned that we are interdependent. My freedom is bound to your freedom, and my peace is bound to your peace. I learned that I am part of a past, present, and future torn by fear and isolation and pain. I learned that when we do the things that scare us, go to places that look us in the eye and ask us to find humanity where we are, and hold the soft underbelly of what makes us laugh and cry and dance and scream (knowing we all dance and cry and laugh and scream) we understand big ideas like liberty and justice and love more

completely. We understand that the I am, the as if, and the not yet include us all.

My Path

I think about the intersection of art and history and resistance as I put the pieces of the B. Mifflin Hood Brick Company oral history puzzle together. My passion is to pay attention and write about the beauty of our world. Our capacity to learn from our past at a deliberate and urgent pace, ask the questions that must be asked, have honest conversations, and build a better world inspires me. I ask about what it means to become human together.

This story draws me in for a million reasons. When we moved to Atlanta, we immediately lived on the Atlanta Beltline — a roughly 22-mile interurban, former railroad track trail that surrounds the core of Atlanta. We live and breathe the Beltline to this day. I wrote piece after piece about Beltline art. I saw the B. Mifflin Hood Brick Company Building, which sits on the Beltline and was immediately fascinated. We then bought a home across the street from the building at around the same time the public art sculpture, Canis Rufus, was installed. I read an article about the artwork and started digging. I wrote a piece and kept digging into the building’s history, the story of B. Mifflin Hood and convict leasing, and Canis Rufus. My path to this work was/is clear. Storytelling that started as soon as I had words, and continued inside the fence, had to continue — oral history as love letter to art, history, and activism.

About Katie

From Louisville. Live in Atlanta. Curious by nature. Researcher by education. Writer by practice. Grateful heart by desire.

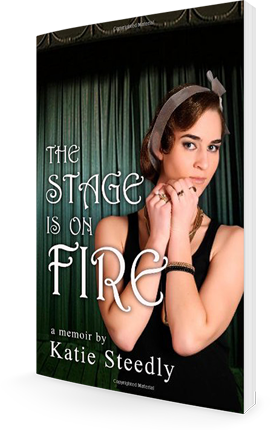

Buy the Book!

The Stage Is On Fire, a memoir about hope and change, reasons for voyaging, and dreams burning down can be purchased on Amazon.